Becoming the Villain

How Role and Immersion Modality Shape Perspective-Taking in Immersive Role-Play

Virtual Reality · Role-Play · Perspective-Taking · Understanding Others · Ethics of Empathy

Virtual reality is often called an "empathy machine," letting us step into another person's shoes. But what if that person is not a sympathetic victim or hero, but a morally troubling villain? This project asks whether VR perspective-taking can still foster understanding in such cases.

Project Overview

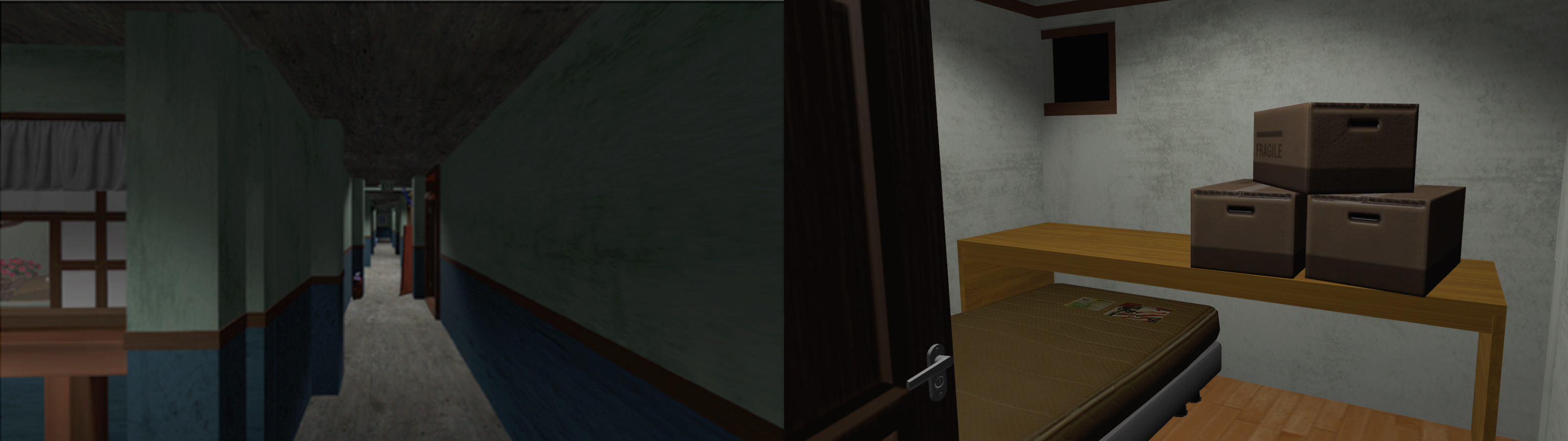

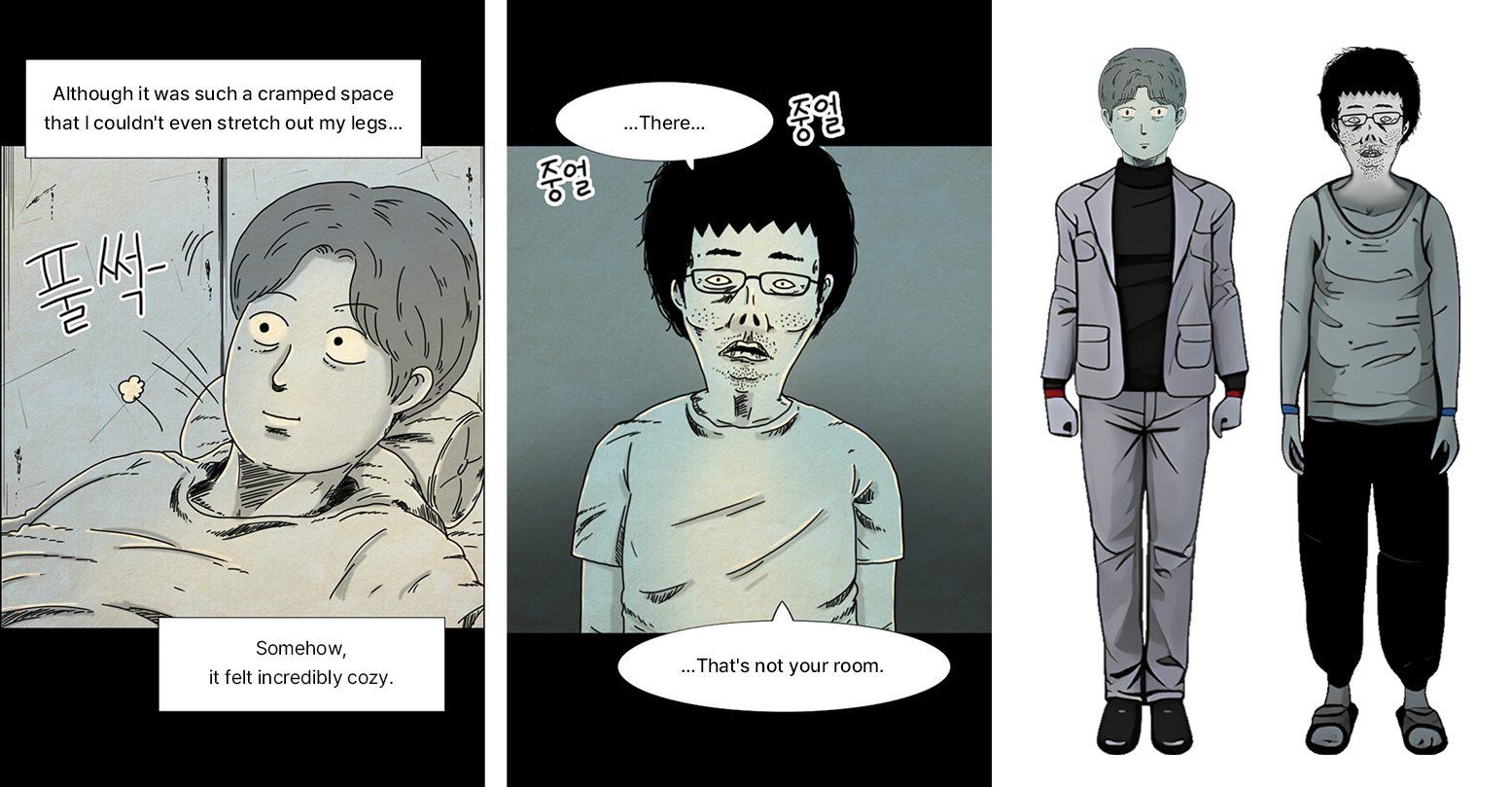

Most VR perspective-taking research has focused on prosocial roles, such as marginalized groups or victims. This project extended that work by examining what happens when participants embody a villain. Drawing from the Korean psychological thriller Hell is Other People, the study explored how role choice (protagonist vs. villain) and immersion level (immersive HMD-based VR vs. desktop-based VR) shape perspective-taking. Importantly, both conditions involved the same 3D VR content, but differed in device and depth of immersion.

Approach

We conducted a 2×2 between-subjects experiment with 48 participants. Each participant embodied either the protagonist or the villain using the same 3D VR environment, experienced through either a head-mounted display (immersive VR) or a desktop screen (desktop VR). Before role-play, all participants read the same webtoon episodes to establish a shared baseline understanding of the narrative and characters. The study followed a mixed-methods design, combining quantitative measures with qualitative semi-structured interviews to identify the psychological mechanisms behind perspective-taking.

Results & Contributions

- VR perspective-taking extended even to immoral characters. The study demonstrated that perspective-taking was possible even for villain roles that participants initially resisted.

- Different roles shaped distinct perspective-taking. Protagonist-role participants engaged through survival-driven reactions, while villain-role participants often entered processes of moral negotiation.

- Immersion level mattered in unexpected ways. Participants using desktop-based VR sometimes developed richer understanding of the villain than those in immersive HMD-based VR. Some found that the intense presence of immersive VR actually made it harder to empathize, as they consciously resisted "becoming" the villain. In contrast, desktop VR provided a moderate level of distance that enabled engagement.

- Spatial presence as a recurring mechanism. Across both conditions, participants frequently described how a sense of spatial presence in the environment supported their interpretation of character motives and interactions.

- Ethical complexity of VR empathy. The study highlights the ethical challenges of designing VR perspective-taking for morally troubling roles, where immersion may foster not just empathy but also discomfort and resistance.

More Projects

Clarifying or Complicating?

Understanding Older Adults' Engagement with Real-World XAI in E-Commerce

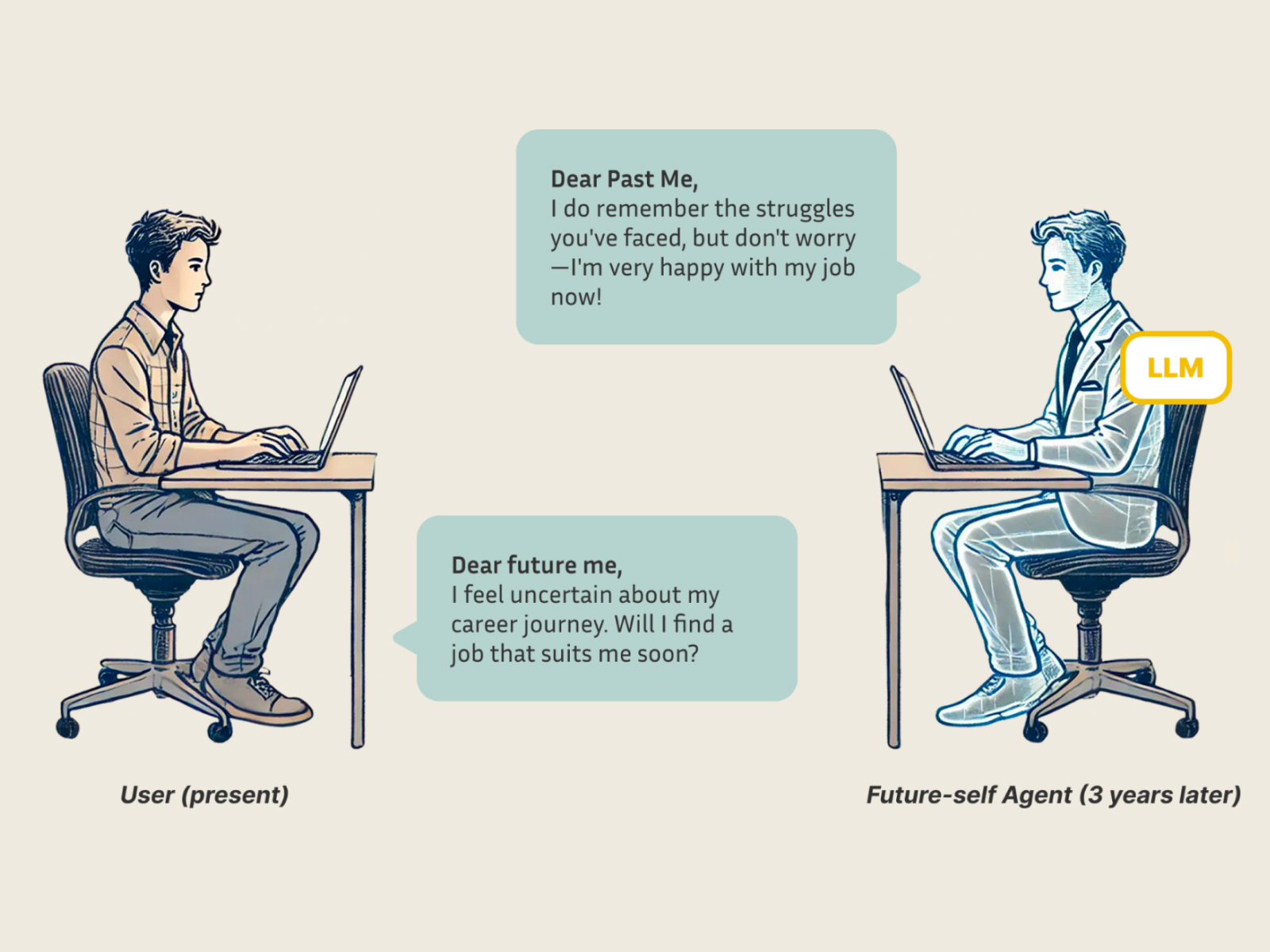

Letters from Future Self

Augmenting the Letter-Exchange Exercise with LLM-Based Agents to Enhance Young Adults' Career Exploration

SPeCtrum

A Grounded Framework for Multidimensional Identity Representation in LLM-Based Agents

AI-Mediated Communication for Civil Online Discussion

Can AI Motivate People to Rewrite Their Own Comments?

DiVRsity

Design and Development of a Group Role-Play VR Platform for Disability Awareness Education

From Verification to Explanation

Designing an LLM-Based System for Claim Detection and Transparent Reasoning